Environmental challenges

2020: The year to take action in favour of biodiversity?

The 2010s was the warmest decade ever recovered since measurements began in 1850, and the trend continued into 2020, with the month of January beating the record temperature and averaging more than 3°C higher than the norm from 1981 to 2010.

There is almost universal agreement on the extent of the climate crisis, as news reaches us of frequent natural disasters, record temperatures worldwide, and a plethora of potential emergency measures to mitigate its effects and help us adapt. The unanimity extends into economic and fi nancial sectors that are gradually becoming aware of just how big the challenge is, thanks to academic research that has quantifi ed the fi nancial impact of failing to act against climate change. In spite of all that, the interaction between climate change and biodiversity is not yet taken up enough in the debate and academic research. Biodiversity has thus far remainedthe poor country cousin of the environmental crisis that we are experiencing, despite its huge contribution to the

exosystemic services needed for our very survival.

THE CONCEPT OF THE NINE PLANETARY BOUNDARIES ILLUSTRATES THE CHALLENGES TO BE MET

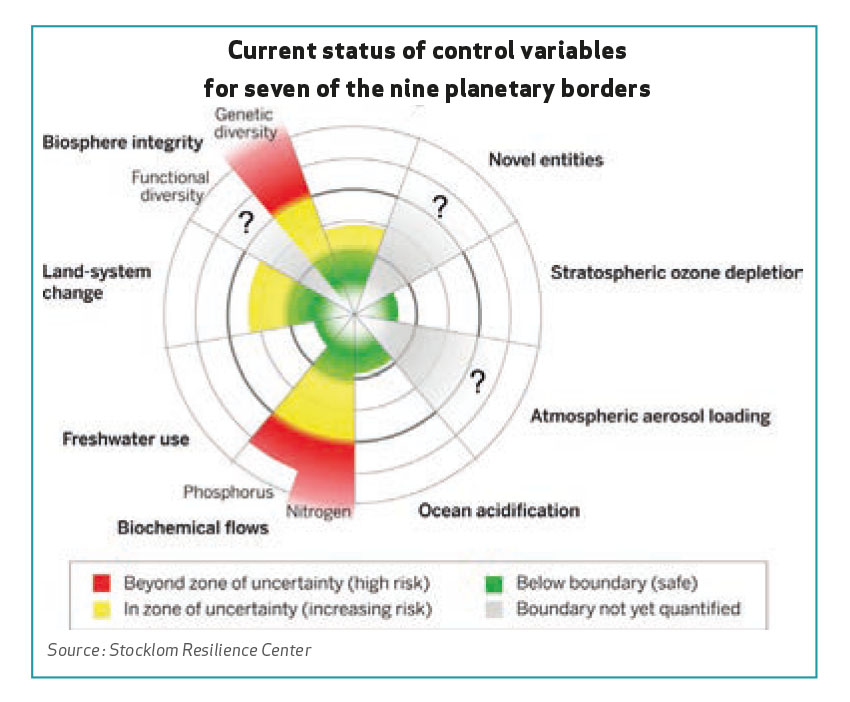

A clear illustration of the emergency arising from the loss of biodiversity can be found in the concept of nine planetary boundaries developed in 2009 by 26 researchers of the Stockholm Resilience Center. This concept identifi es the limits that humanity must not surpass to keep from compromising its development and its survival on the planet. Scientists have managed to quantify thresholds for seven of these nine limits.

We have already exceeded these thresholds in three planetary boundaries – erosion of biodiversity, climate change, and disruption of the biochemical cycles of nitrogen and phosphorus, as seen in the illustration below:

The breach is even more spectacular in erosion of biodiversity (red zone) relative to climate change (zone jaune). This was the urgent message of the latest report, dating back to May 2019; of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, (IPBES), which is the biodiversity equivalent of the IPCC.

The breach is even more spectacular in erosion of biodiversity (red zone) relative to climate change (zone jaune). This was the urgent message of the latest report, dating back to May 2019; of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, (IPBES), which is the biodiversity equivalent of the IPCC.

The scientific community agrees that the sixth mass extinction is under way and that it is due to human activities. Of the 8 million animal and plant species living on the planet, up to 1 million are threatened with extinction in the next few decades. This speedier vanishing of species is disrupting the function of natural ecosystems considerably, including all the eco-systemic services that benefi t humanity and that it needs to survive and thrive.

PRICING BIODIVERSITY IS A NECESSARY STEP TOWARDS PRESERVING IT

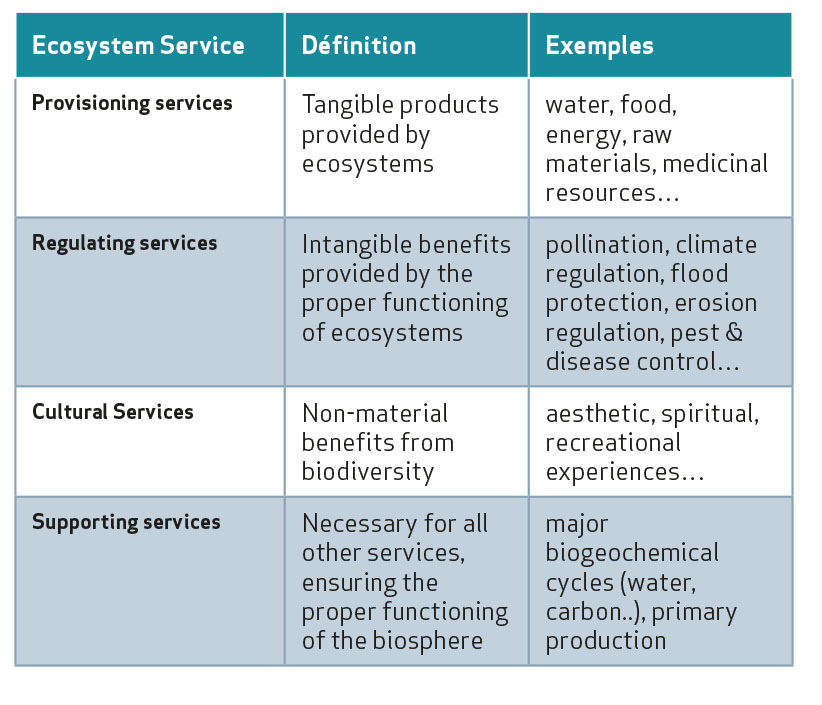

Four types of eco-systemic services have been identified :

The economic value of these services was estimated at between USD 125,000 and USD 140,000 billion in 2014 and this figure is still used as a benchmark today, even though it is underestimated by far, given the speed of the deterioration and the difficulty of economic measurement.

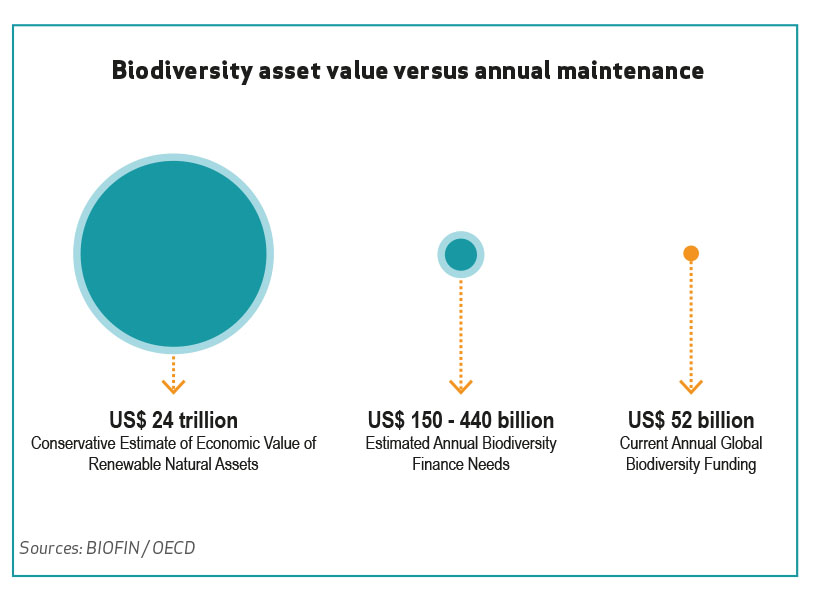

The UN’s Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN) estimates annual funding needs to restore biodiversity at between USD 140 and 440 billion. The estimated USD 52 billion in actual spending is still far below this range. The funding gap is big and even bigger when compared to the USD 500 billion in annual subsidies allocated to activities that threaten biodiversity, such as fossil fuels and intensive agriculture.

These figures highlight the urgency of taking action to counter the decline in biodiversity, which is even more alarming than the effects of climate change.

These figures highlight the urgency of taking action to counter the decline in biodiversity, which is even more alarming than the effects of climate change.

Even so, little action is still being taken to promote biodiversity and that action gets little support from the economic and financial community, despite the disastrous figures at hand. Why is this?

Action to counter climate change got a big boost in the wake of the Paris Agreement signed in 2015 during the COP21 conference. Further momentum came with the publication of research backing the financial materiality of climate change and the development of several reporting standards, including the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), which has become the global standard in disclosure.

There is still a long way to go on the issue of biodiversity, which still needs a major thrust to push it into the spotlight. Here’s hoping that this will happen in 2020, with the COP15 on biodiversity being held in China in October, calling on governments to set clear targets in protecting nature during this decade of 2020-2030.

IT IS CRUCIAL TO DOCUMENT THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF THE DECLINE IN BIODIVERSITY

Very little intensive academic research has been done on the economic and financial impact of the erosion of biodiversity, due, among other things, to the difficulty of boiling down the highly complex issue of biodiversity – with a multitude of eco-systemic services involved – to precise indicators.

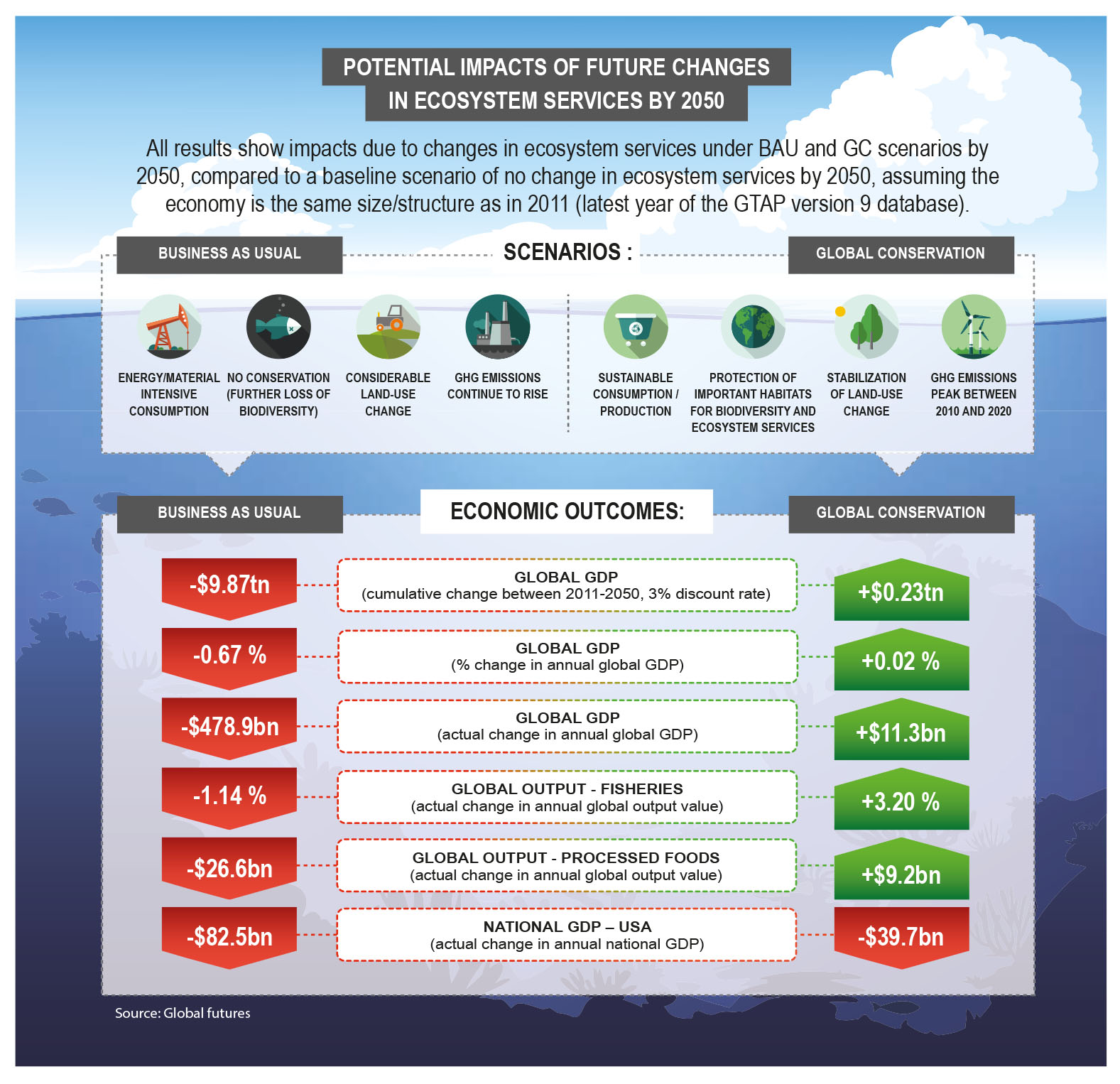

Even so, this difficulty was partly alleviated with the February 2020 publication of the “Global Futures”, an initiative borne of a partnership of the WWF, Purdue University’s Global Trade Analysis Project, and the University of Minnesota’s Natural Capital Project. The study – a global first of this extent, which required two years of work – set out to quantify the economic cost of the decline of biodiversity in 140 countries and several key economic sectors, by combining a global economic model and land-use models with high-resolution eco-systemic services. This initial approach of “integrated modelling of the decline in biodiversity” is a major step forward in integrating materials and now quantified biodiversity risk, into financial risks.

As with IPCC scenarios, three scenarios were used – “Business-as-Usual”, “Sustainable Pathway” and “Global Conservation”, which is the most optimistic scenario, describing effective global coordination on the climate emergency and land use, as well as the allocation of a large proportion of land to creating protected areas.

For a proper understanding of the study, it is necessary to keep in mind some details on methodology:

- Only six ecosystems are included: the supply of water for agriculture; supply of timber; marine fisheries; pollination of crops; protection from flooding, storm surges and erosion; and carbon storage to help protect us from climate change. They were selected as they have a significant economic impact and are sufficiently documented by academic research.

- The quantified economic impact may be partial (concerning water supplies, only the impact on farming was calculated and not the impact on supply of drinking water or human health).

- The model is unable to integrate the exponential impact of the crossing of major tipping points that generate irreversible effects and, potentially, the total failure of an eco-systemic service.

These methodological details are worth pointing out, as they show how extremely conservative the findings are in terms of economic cost. The expansion in the number of services analysed and the probability of reaching tipping points will raise economic cost significantly.

Even so, the findings are unequivocal. The “Business-as-Usual” scenario would lead to the destruction of USD 479 billion annually until 2050, including USD 327 billion from the decline of coastal areas and USD 128 billion in losses of carbon sequestering.

The United States is the most affected in absolute terms, with an annual loss of USD 83 billion, followed by Japan and the UK. France ranks eighth, with a loss of USD 8.4 billion, due mainly to the erosion of coastline and fisheries.

However, developing countries are the hardest hit in terms of percentage of GDP, with -4,2% for Madagascar and -3.4% for Togo. As is the case for climate change, vulnerable persons are the main victims of the decline in biodiversity, as this widens global inequalities while humanity faces new challenges.

It is becoming urgent to take stock of the cost of doing nothing about declining biodiversity and to adopt a more holistic approach to the socio-environmental crisis, beginning by simultaneously integrating climate and biodiversity risks, which are now two sides of the same

coin.

The COP15 on Biodiversity held in China in October 2020 will, without a doubt, be decisive in progress on integrating biodiversity risk into economic and political decisions.

In the meantime, a growing number of initiatives on integrating biodiversity into economic models are emerging. The latest of these is the joint PWC-WWF publication Nature is too Big to Fail, released in January 2020 and proposing a classification of financial risks linked to biodiversity, based on the example of climate risks (including transition risk, physical risk, litigation risk, and systemic risk) and a series of recommendations for governments, financial regulators, central banks, and other financial players.

A coalition of four asset managers early this year launched an appeal to develop a tool to measure biodiversity’s impact. And in May 2019 Axa and the WWF jointly called for the creation of a TCFD for biodiversity, a “task force on nature impacts disclosures” that would integrate and analyse the risk posed by declining biodiversity.

— Mériéme Boutayeb, Strategic Marketing & Projects, CPR AM