Demographic & social challenges

Cross-generation inequality: are schools the first to blame?

Five generations. On average, this is how long it takes a descendant of a poor family in the 24 countries of the OECD1 to achieve the average national income. Although the notions of equal opportunity and merit are at the heart of every democratic society, inequality has been allowed to persist. Decoding of a global phenomenon that starts with the education of a society’s future citizens.

THE TRANSMISSION OF POVERTY, IN FRANCE AND ELSEWHERE

In 1964, Pierre Bourdieu published a book entitled “The Inheritors” (Les Héritiers). Highlighting the relationship between cultural and symbolic domination, the sociologist showed how working-class people were virtually excluded from universities: at the time, less than 1% of the sons and daughters of agricultural laborers became students, compared to 70% of the offspring of business people and 80% of the liberal professionals. More than 50 years later, the situation has sadly remained unchanged. Inequality has continued to fl ourish around the world, and particularly so since the 1980s. While Europe is one of the continents that has best resisted, the gap has nevertheless increased in every country2.

The disparities are first geographical. In France, for example, the Paris region, the west and a large part of the southwest are doing bett er. In contrast, three regions in particular are struggling: the northeast, the areas by the Mediterranean coast and the Garonne Valley, between the towns of Toulouse and Bordeaux. “These regions are characterized by higher rates of unemployment, more single-parent families and and more young people without qualifications,” explains Hervé Le Bras, a specialist in demographics and migration. “In practice, these disparities create their own system – where young unqualified people are at greater risk of unemployment which, in turn, increases their risk of divorce and family breakdown, etc.” This downward spiral is effectively selfperpetuating, from one generation to the next.

And yet, the state is playing an active role in trying to reduce these disparities. Hervé Le Bras, the author in 2019 of “Feeling bad in a France that is doing well3”, showed that inequality is less pronounced there… despite common perception is the opposite. “The poor in France are less poor, because the share of GDP that goes to social services (34%) is higher than elsewhere,” he wrote.

SCHOOL, AN ELEVATOR FOR SOCIAL MOBILITY CURRENTLY STATIONARY

Despite this willingness on the part of the state to act, inequality is clearly persisting. Thinking about this phenomenon involves taking a close look at the key mechanism of our meritocratic ideal: our schools. International studies (notably PISA) show that the French education system is one of the most unequal, and the most likely to pass it from one generation to the next. Research by the country’s Ministry for Higher Education recently analyzed the educational journey of a single generation4. At 15 years old, pupils origins were an accurate reflection of the working population composition: the children of workers and employees represented 50% of the workforce and outnumber by three the children of senior executives (17% of the total). Three years later, the distribution was very different. Only a third of those who sat their final school exams were children of workers and employees. This trend is further accentuated when it comes to higher education: with 55% of the children of senior executives getting a Masters degree, compared to 23% of the children of employees and just 13% of workers’ children. This example from France can be extended to all countries.

SCHOOL AND LOCAL AUTONOMY: IDEAS WORTH PURSUING

What can be done to prevent inequality from one generation to another? Probably by starting out with an in-depth reform of one of the corner stones of our society: schools. In France, for example, everyone seems to agree with the evidence. One government aft er another has taken measures to try and deal with this tricky problem. The task is vast and requires a very detailed work over the long term. “The first types of inequality are between schools themselves,” remarks Hervé Le Bras. “A major step forward would be to burst the social bubbles in which people live.” He cites the example of ‘busing’, a solution implemented in the United States in the 1960s to fight racial segregation. Every morning, all pupils were taken to school by bus, with the aim being to have an equal share of white and black students in each school.

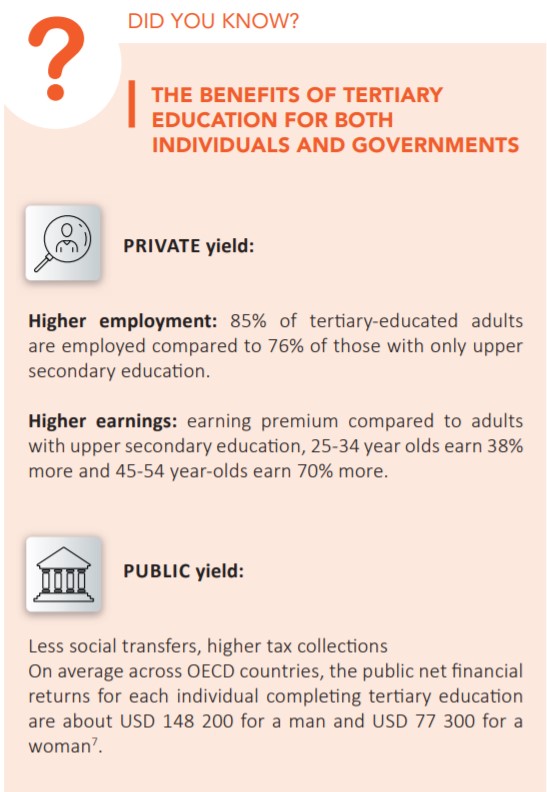

Several studies in the United States underline the fact that an employee’s qualifications is one of the main reasons for the widening gap between rich and poor. “As the American education system has been struggling to educate more highest-qualified employees, their rarity has led to a much higher rise in their earnings than in the rest of the population,” explains Alain Trannoy, an economist and research director at France’s School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (EHESS)5. The rise of the internet and IT tools has merely served to increase those qualification levels differences. “The only solution is to invest massively, so that the majority of an entire generation is pushed towards achieving the highest levels of qualification,” he claims.

Clearly, education already has one of the biggest government budgets. According to Eurostat, average spending on the sector by European countries was 4.6% of GDP in 2017 (6.8% in Sweden, 5.4% in France and 4.1% in Germany). In cash terms, such percentages can exceed a hundred billion euros a year… and potentially even more if countries are able to reduce their shortfalls.

To solve the problem of growing inequality, Nicolas Duvoux6, a specialist in the subject, makes a connection between progressive taxation and success in combating tax avoidance.

“The way a country can correct inequality within its borders partly depends on what its neighbors are doing,” he points out. “Aside from the losses sustained by the state, tax avoidance is a threat to the fairness on which society is based.” Put simply, people react badly to progressive taxation if they see that others spirit their money out of the country without paying their taxes. Coordinated international action in this area would therefore seem more than ever essential.

Another option could be to provide more autonomy at the local level. Hervé Le Bras believes that the state should not only perform the role of a financial leveler – where the richest regions help the poorest ones – but should also devolve more autonomy to the regions. The basic idea being that fighting poverty in the same way everywhere is simply illusory. Social structures, the role of local industry, the local history… all these elements are specific to an area, and local organizations are the best placed to deal with them. Here again, strong political commitment could be a way of limiting the degree to which inequality is passed from one generation to the next… and thereby prevent one of the foundations of our democracies from becoming imperiled: the promise of truly equal opportunity.