Economic shifts

China, a development closely linked to demographics

Demographic pressure is one of the keys to understanding China’s political and economic decisions over the past 30 years.

The impact of the single-child policy

China’s population is currently 1.3 billion, or one fifth of all of humanity. This has been a major constraint in its development, in that China has given precedence to unskilled-labour-intensive sectors and, more to the point, low-labour-cost sectors. China also has a major edge in that 70% of its population is of working age (15-

59 years). So it has an exceptionally low proportion of economically dependent people (i.e. children and elderly people). The one-child policy, which was instituted by China from 1979 to 2015 in order to control its population, has led to an unprecedented decline in its birth rate, to 12 for 1000 today in China (vs. 11.4 in France, based on the provisional estimate of INSEE, the French national statistics agency, and 10% for the 28 countries of the European Union).

The one-child policy has been eased over the past several years (especially beginning in 2013), and, since

1 January 2016, all couples have been allowed to have two children. But it is far from certain that eliminating the one-child policy will help increase the birth rate. While the birth rate has stopped falling, it is not truly moving back up.

This policy put through by Deng Xiaoping aimed for a hands-on improvement in living standards. And, indeed, living standards have improved in the past 30 years, with 500 million people being lifted out of extreme poverty, according to the World Bank. Per capita GDP (on a purchasing power parity basis) has risen from $677 in 1986 to $15,394 in 2016, according to the IMF. However, based on Chinese standards of poverty (i.e. RMB 2,300 in annual per capital income in rural areas at constant prices), 55 million people were still living in extreme poverty in 2015.

The new economic and social environment: very rapid ageing

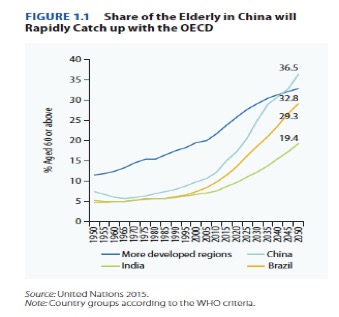

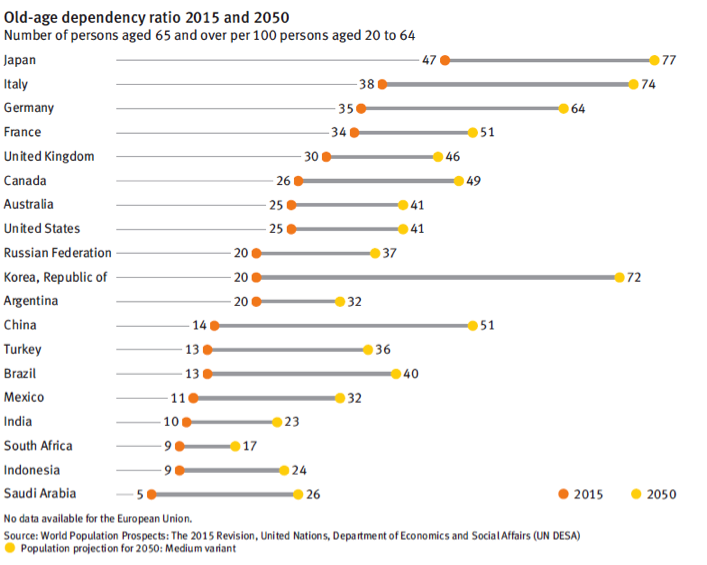

Falling fertility rates and longer life expectancies continue to disrupt China’s age pyramid. That’s why the authorities are becoming concerned over demographic ageing, which is expected to be extremely rapid. By 2050, China will have 220 million fewer people of working age than today. A labour shortage is already looming in some sectors. In more immediate terms, the working population has been declining from year to year since 2016. Today there are five working people per retiree. By 2040 there will be only 1.6.

According to the United Nations’ demographic projections, the percentage of people aged 65 or more is expected to have tripled, from 7% in 2000 to 24% in 2050, when China will have 330 million elderly people. Another characteristic is likely to disrupt Chinese society – the shortage of women. China is one of the world’s few countries in which men are in the majority: 104.9 men to 100 women in 2010. Chinese society’s preference for sons goes back to patriarchal traditions and Confucianism, which keep women in secondary roles in society and the family. Sons perpetuate the family line and are duty-bound to take care of their parents in their old age. Moreover, as there is a strict limit on the number of children couples can have, daughters become undesirable simply because they deprive parents of the possibility of having a son.

Clearly, taking care of the elderly will be a big challenge for Chinese authorities, as for most poor people the family is the only system of “social welfare”. In the mid-2000s, only one retiree out of four lived off his pension. Another quarter continued to live off a wage, while the remaining half subsisted mainly thanks to a member of the family, often a child. In certain ways, the family model continues to receive official encouragement. A 1996 law requires children to support their parents. But their lifestyles, including increasingly expensive urban homes, are not conducive to intra-family assistance. For example, to find work, young people move far from their home region. China’s special demographics also explains why its savings rate is so high (46% of GDP in 2016 vs. a global rate of 26%, according to the IMF). People feel they have to save for the future, given the lack of a universal public pension system.

China got “old” before becoming “rich”

In contrast to many other countries, China’s demographic trends have paralleled its economic development. Traditionally (as in Japan and South Korea), fertility rate trends downward after an economy takes off, producing changes in society. This happened before the economic take-off in China, due to political imperatives. These imperatives have now been eased or eliminated, but, for families, the die is cast, especially those families who live in cities and have economic priorities that are not very compatible with having many children. China is still far from having reached the level of wealth of major developed economies. One measure of this is healthcare spending as a percentage of GDP, which is far lower (at 5.6% of GDP) than in France (11%) and the United States (16.6%, based on 2014 figures). The state funds only 55.8% of healthcare spending, vs. 78.7% in France but just 49.3% in the United States.

By 2035, 30% of China’s total population will be older than 60, the same as in developed economies. But its living standards will not be the same, with per capita GDP about one fifth of that of developed economies. The challenge for the authorities is to adapt the Chinese economic model to this demographic constraint while meeting environmental challenges as well. This demographic constraint is why China absolutely needs to switch from a growth model based on exports of low-value-added goods to an inclusive growth model based on services and innovation. Official statements now focus on the quality of growth and no longer its quantity, sustainability and, more of all, its ability to benefit large swaths of the population. Thus far, the Chinese model has led to wide inequalities, territorial ones in particular, which have been only partly offset by entitlement payments.

Demographic imbalances could also lead to social tensions. Unlike Japan, Chinese society is not homogenous, and higher population growth among minorities could lead to unrest. An older population will have greater needs in services, another possible source of unrest.

Demographics are the key to China’s economic orientations and will inevitably have an impact on the rest of the world.

All growth objectives must be seen through the prism of this demographic constraint. A growth model based on promoting exports of low-value-added goods has brought about a first phase of development. But it ran into its economic, social and environmental limits early in this century. A transition is needed towards a consumption-based economy of services, a transition that factors in the notion of sustainable development.

It was with the 11th Five-Year Plan (2006-2010) that the authorities made satisfying domestic demand a key objective of economic policy. Developing the human factor is now a priority. China’s massive pool of labour is draining little by little. Wage hikes far higher than productivity gains are eroding its competitiveness. So productivity must be raised through research and development and by strengthening human skillsets. All this has a cost in terms of public spending, even as the rapid ageing of the population requires a true public universal old-age pension policy, which is currently far from being the case.

China’s determination to spread its political and economic influence beyond its borders (“One Belt, One Road”) may also be due to the need to make use of a broader and cheaper workforce in a country where there is little immigration.

Let us recall that all official political and economic measures must meet various target dates. One such date is 2021, the centenary of the establishment of the Chinese Communist Party and the target date for achieving a “moderately affluent society”, including the doubling of per capital GDP from 2010 levels. Another target date is 2049, the centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, with the objective of “a modern socialist country that is prosperous and strong”. Meeting these objectives will require continuing to reform the Chinese economic model. The first years of China’s transformation have had a major impact on the rest of the world due to its sheer size – which accounts for 18% of global GDP and one third of global growth.

— Laetitia Baldeschi, Head of Strategy Team, CPR AM